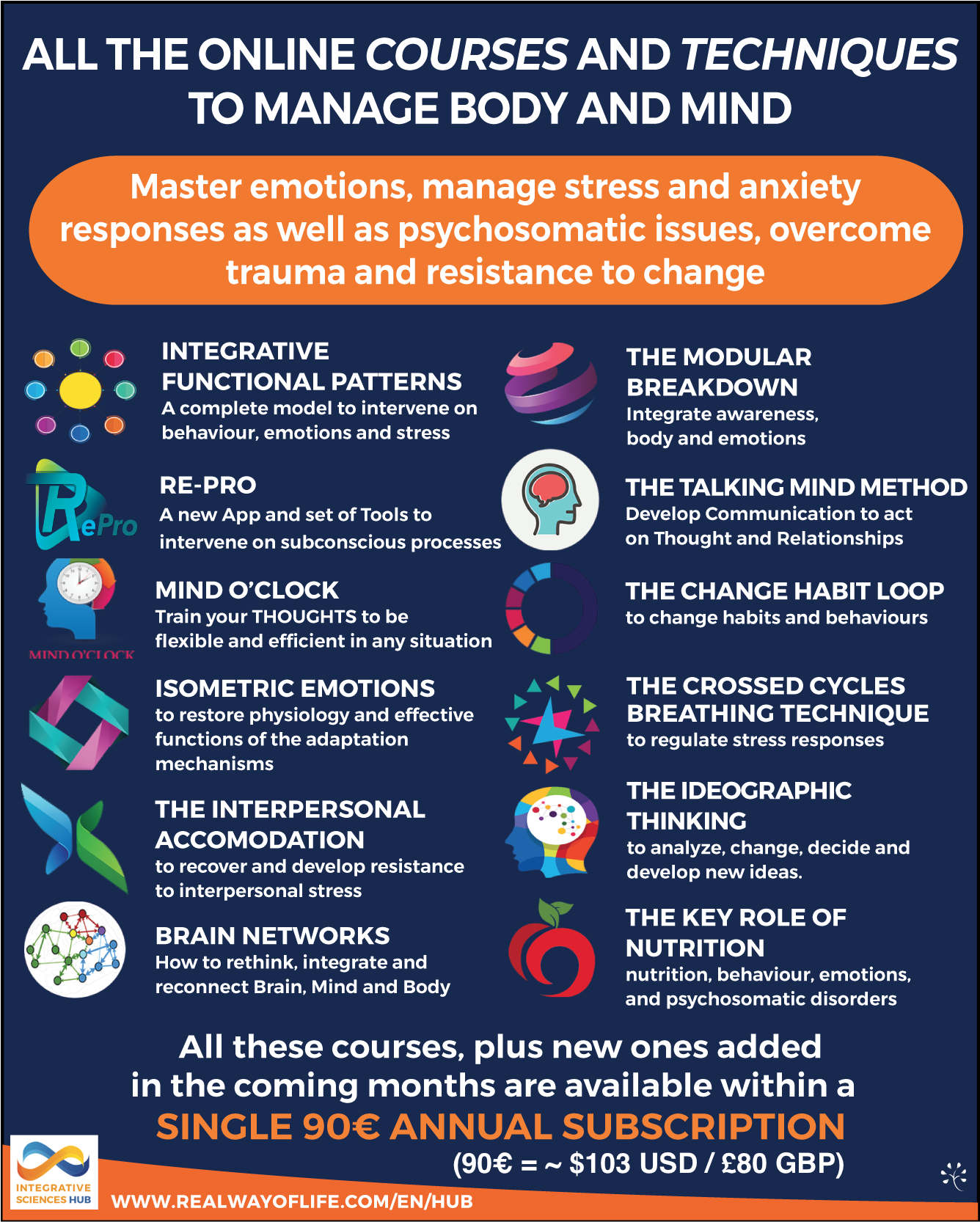

12 Feb How to regulate emotions and relationships bottom-up (time, context, physicality, schemas, etc.)

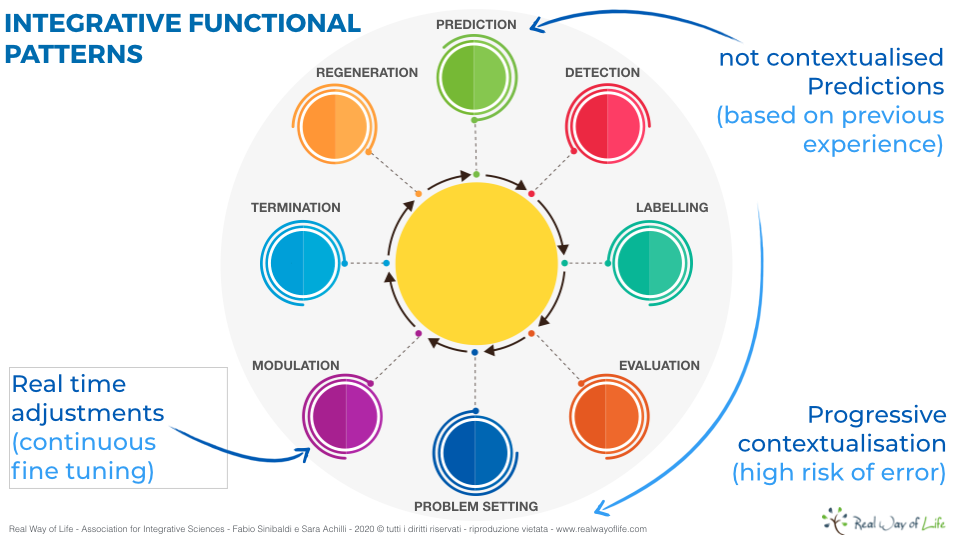

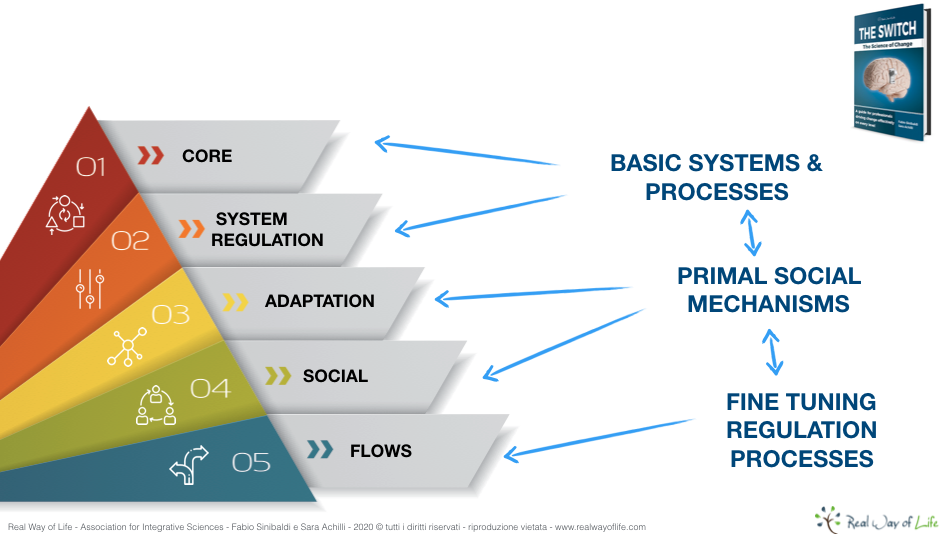

Interpersonal regulation and its connection to emotions, safety, self-regulation and immune system processes features a series of evolutionary systems that have been refined over time to help contextually manage the present in real-time.

One typical example from daily life is provided each time that we receive a message or an email on our smartphone. If the content sounds aggressive – a personal slight, a lack of respect for our professional self or the imposition of something we do not deem right – our immediate reaction is to reply in the same tone, defending ourselves or returning the aggression.

One typical example from daily life is provided each time that we receive a message or an email on our smartphone. If the content sounds aggressive – a personal slight, a lack of respect for our professional self or the imposition of something we do not deem right – our immediate reaction is to reply in the same tone, defending ourselves or returning the aggression.

If we give in to this instinct it is common to feel a momentary sense of relief and then to remain suspended as we await a signal of victory or a counter-move to respond to.

If, instead, we do not respond, it is likely that we will continue to go over and over what we would like to write, trying to provide the anger and aggression that have been triggered with some release.

The dysfunctional aspect of this process is that our system for the management of invasions, conflicts and challenges has evolved over centuries to manage a real, physically present adversary whose behaviour we can read in non-verbal behavioural traits, whose changes in attitude we can see and can connect to the overall context. By interacting in synergy with these manifestations we take part in a dual interaction whose objective is to transform reality or the status of the relationship. These are deeply rooted process that humans have in common with all mammals (Crofoot, 2010).

-> Discover the Integrative Functional Patterns.

In a different, but equally evocative, way we have all experienced primitive protection systems that impose themselves on logic – literally bypassing it. Think about when an insect or a bird hits the windscreen of your car for example: your mind is well aware that the windscreen is much more solid than these little creatures, but your safety system makes you wince and cover your face with your arm (Sinibaldi and Achilli, 2016).

These observations do not make any less interesting the analysis of higher or more sophisticated logic and forecasting systems, or of projections into the past and future of interpersonal relationships and their value. On the other hand, it is important to highlight that to manage and help these sophisticated processes it is critical to intervene on the lower level switches that support them and/or enable their activation.

-> Discover the Switches of Change.

It therefore becomes useful to note the importance of the effect of context, of combinations and of various other primary elements on interpersonal interaction processes.

Research has in fact extensively highlighted how context can influence emotional perception: scenes seen, voices heard, presences, people’s faces (even when there is no direct interaction with them), cultural setting, the employment of certain words as opposed to others, can all radically change the evaluation that is made of the emotional impact of a face (Barrett, 2011). This perspective debunks various preconceptions such as those relating to the innate ability to read emotion on someone else’s face. This is a skill that should not be confused or mixed up with other adaptation processes such as the ability to immediately subconsciously identify higher or lower danger configurations on someone’s face. This information is then integrated and processed along with other external clues and information relating to internal resources to come to a decision as to how to behave socially.

Emotional-interpersonal dynamics can be brought back to their physiological state and then improved upon by using certain strategies:

- Exercising the skill of finding and evaluating relevant contextual clues that are often erroneously pushed into the background while focusing on our counterpart;

- Actively managing the time-span of events by methodically looking at correct and real connections between facts and judgement and vice versa, unreal or incorrect ones;

- Introducing beliefs and expectations in this wider representation and seeing them as components that in part contribute to evaluation and forecasting although they are not conclusive in themselves;

- Moving along different time scales, increasing and reducing the time lapse considered and evaluating how this can radically change the evaluations started, the emotional experience triggered (not to be confused with past ones, as correctly highlighted by Khaneman) and subsequent behavioural choices.

Right at the start of the twentieth century the Russian film director Lev Kuleshov perceived how an emotional, affectionate and interpersonal tone in a scene could be evoked by contextual clues and by the tone of the scenes immediately preceding. Recent neuroscience studies (Calbi, 2017) have proven this idea correct and shown the huge difference between static images (often used in research but also in emotional education), and dynamic images (videos) that are far more powerful and effective as they reflect more closely the natural process of interpersonal adjustment in real life. This has critical fallout on methodological choices in clinical and educational practice.

Barrett, Lisa & Mesquita, Batja & Gendron, Maria. (2011). Context in emotion perception. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 20. 286-290. 10.1177/0963721411422522.

Calbi, M., Heimann, K., Barratt, D., Siri, F., Umiltà, M. A., & Gallese, V. (2017). How Context Influences Our Perception of Emotional Faces: A Behavioral Study on the Kuleshov Effect. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 1684.

Crofoot, M. C. & Wrangham, R. W. in Mind the Gap: Tracing the Origins of Human Universals (eds Kappeler, P. M. & Silk, J. B.) 171–195 (Springer, 2010).

Sinibaldi F., Achilli S. (2016) Transformative Mindfulness: 45 exercises. An idea-a-day workbook to develop awareness and favour change. Real Way of Life.