01 Aug Favouring EVOLUTION, LEARNING and DEVELOPMENT: what neuroscience tells us and how to put it into practice

Evolution, learning and development represent an essential part of our lives, as both individuals and members of society. These phenomena don’t only regard children, but continue—with different characteristics and to satisfy different needs—throughout our life.

Curiosity, knowledge and the development of new skills are rooted in us. They represent adaptive modalities that we have developed over centuries of evolution. They are part of what we have defined as Evolutionary Behaviours (you can find further insights in the blog and in the book The Switch – The Science of Change).

Recent neuroscientific discoveries have shed light on some very interesting aspects of which we weren’t aware before, that have significant practical implications. How aware are we and how much are we using them to our advantage? How have the educational systems, from the basics of primary school to the more sophisticated training sessions for adults, moved so far? Are we giving due consideration to how thoughts, learning, decision-making processes, culture and neurobiological bases have evolved?

Let’s look at this in more detail.

Emotions and Rationality: friends or enemies?

Emotions and cognition are two strictly interrelated aspects. To be precise, no matter how useful it is to make a distinction between the two in order to study them properly and make things clearer, it is not possible to keep them separated.

In fact, emotions include sensory and cognitive processes. In the same way, the cognitive aspects implied in education—like learning, memory, decision-making, motivation and social functioning—are influenced by emotions and, in turn, are an integral part of their processes.

Emotions require the perception of a relevant emotional trigger (either a real or imagined situation) that has the power to activate an emotion and its physiological correlative, that activates changes in body and mind.

Emotions require the perception of a relevant emotional trigger (either a real or imagined situation) that has the power to activate an emotion and its physiological correlative, that activates changes in body and mind.

These changes in the mind include, among other things: focusing attention, recalling relevant memories, learning the association between events and their consequences, and these are all fundamental processes for education, learning and development.

In this analysis we must consider that emotion-free rational thinking and logical reasoning can (with difficulty) exist in certain experimental conditions. However, in the real world it is not possible to use these two skills entirely and effectively if there are no emotions.

There is a wide area of overlapping between cognition and emotion. These are mechanisms that regard learning, memory and decision-making processes, in both the individual and social spheres. Only this type of complex interaction is able to support thoughts in the richness of creativity, innovation, social intelligence, ethical decisions and motivation.

The factors involved (and the interfering factors)

Cerebral area, stress and hormones

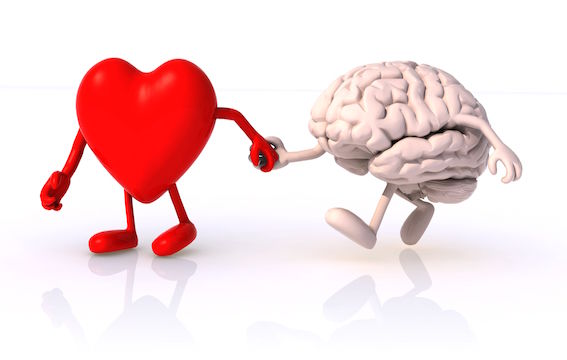

There are different cerebral areas involved in these processes and it is extremely fascinating how both the writing and recovery of memories are strongly influenced by organs and neurotransmitters that also elaborate and mediate emotional responses.

For example adrenaline, noradrenaline and cortisol are among the hormones that are triggered in the responses of adaptation to the environment, from physiological stress to traumatic experiences. Excessive (or too scarce) quantities of these neurotransmitters can significantly alter our ability to memorize and remember.

Organs like the amygdala, the hypothalamus and the hippocampus have a central role in the regulation of emotional and social responses.

Organs like the amygdala, the hypothalamus and the hippocampus have a central role in the regulation of emotional and social responses.

They all simultaneously “tag” memories in a way that favours their correct process and makes their recovery easier.

A hyper- or hypo-stimulation of these organs alters their functioning.

This non-functional stimulation can stem not only from stressful or traumatic events, but also from a sensory or cognitive overload. For example, in order to understand how much we are altering these processes, think of the way those areas of the brain now interact with digital information and social networks, as compared to the physiology for which they were originally developed, and how our brains have adapted over the last decade of digital technology).

The deep power of emotions

Relationships also play a role in these processes. For example, the typical education provided by our western culture focuses on individualistic and competitive aspects that don’t respect the “social” predisposition of our brain with respect to learning.

As mammals, we have evolved over time with social organizations that are essential to our development and survival, starting from the family nucleus, passing through groups of equals, up to associations, working groups, etc. There are specific affective, emotional and mental mechanisms that support our reciprocal attachment, trust, inclusion and cooperation. These are winning and advantageous modalities in most cases.

In a well-consolidated group everyone benefits and is happy to participate. This is true for humans as well as for groups of animals, with which we share—not by chance—many neurobiological structures and processes that mediate these mechanisms.

In a well-consolidated group everyone benefits and is happy to participate. This is true for humans as well as for groups of animals, with which we share—not by chance—many neurobiological structures and processes that mediate these mechanisms.

Unfortunately, our culture has not taken these aspects into great consideration, regarding learning and performance, favouring instead more individualistic attitudes..

Playing games is at the base of natural learning, but our culture looks at seriousness and duties as starting motivational factors, while these, so as not to be experienced as coercions, should be learned from experimentations and from examples.

Also, when it comes to the role of the pack leader, often the innate mechanisms available are not followed. In fact, in nature the pack leader is recognized for his worthiness and value and his/her leadership is never imposed on the pack. How much time do parents, educators and teachers invest in order to be recognized as worthy of their leadership role? Does it seem like a difficult investment to make? It can seem so, if we are not used to doing it, but it is ultimately less difficult than shouting, fighting, challenging one another and remaining disappointed

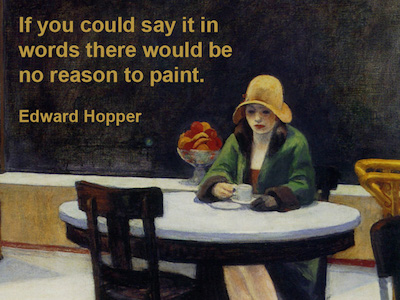

Beyond verbal thinking

Often the mode we tend to consider as more logical and effective is verbal thinking, but isn’t actually so. Emotions are initially triggered by a sensory perception, which is often, but not always, visual. However, in the beginning, emotions are non-verbal. Attributing a name and a thought to an emotion can help to give it a shape, slowing it down and limiting its boundaries. Our thoughts are a lot more than the flow of words that we have become used to as adults.

We have been used to thinking through images and sensations since childhood. Both these levels have a richness and complexity of degrees that can be only partially described by words. On the other hand, a system that simplifies and makes the representation capacity faster is necessary in order for us to communicate, evaluate and decide rapidly. It becomes essential to find a meeting point between the benefits of verbal thinking and the one of images and sensations.

We have been used to thinking through images and sensations since childhood. Both these levels have a richness and complexity of degrees that can be only partially described by words. On the other hand, a system that simplifies and makes the representation capacity faster is necessary in order for us to communicate, evaluate and decide rapidly. It becomes essential to find a meeting point between the benefits of verbal thinking and the one of images and sensations.

A good mediation process is represented by visual and conceptual maps, which have become quite popular since the 70s. These maps “clean” the excessive morbidity of thoughts, but still act on a very cognitive level. To develop the maximum communicative expression and favour a complete and effective representation of thoughts, emotions and relationships, over the last years we have developed a technique called Ideographic Thinking.

This is a cross-sectoral tool that can be used to study, take notes, develop a group project, analyse a complex case and communicate effectively. The basic idea is to exploit the communicative power offered by lines, colours and shapes in a way that is available to everyone and not requiring artistic skills. Rather, we aim at an intuitive representation system that is innate in all of us. In fact, if we think about it, iconic communication has contributed to the great success achieved by Apple and Windows in the past, and of smartphones in more recent years, and no one had to explain that an envelope symbolized messages.

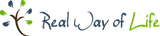

The Ideographic Thinking is be part of the Integrative Sciences Hub.

The power of the body

In these dialogues between emotional and cognitive factors, bodily aspects also play a key role. The modification of muscular tension, but also sensory perceptions (from temperature to flavours) can create and support sensations able to modify the emotion–thought channel. These processes can be dysfunctional, or used actively to reach our objectives. We have already talked about this in detail in a former article that you can find here.

Pursuing choices that are truly rational

Only through a combined analysis of the synergy between emotions and thoughts, is it possible to fully understand well how they work and how to favour learning, educational and development mechanisms.

Often the most ambitious educational wish is the one of teaching somebody else to make the right choices. Before doing this, it would be correct to understand how we make choices and how truly rational and conscious we are of the steps we go through before actually take the decision.

For example, there are many studies that prove how the evaluation of a highly-charged moral event that carries an intense emotional charge where caution is thrown to the wind (eg. stealing, sexual deviation/abuse, physically lashing out with rage), can happen in a fast and unconscious way, while the perpetrator looks for rational proof to justify his/her position only after the fact.

In those who decide so rapidly, the passage from step 1 to step 2 is so fast that it is even difficult to perceive, but neuroscientific investigating tools well identify this gap, which is not present in other choices that are made more slowly and consciously.

Our ability to decide is influenced by the presence of others, even if sometimes in an unconscious way. In other cases, the linguistic form that is used to ask a question, changes our decision. There are also other factors, less deducible, where mind and emotions need to collaborate to avoid being fooled.

Let’s make a real everyday example: have you subscribed to a magazine recently? If so, you will have probably noted a strange type of offer, for example: the online version offered at only 10 euros, the printed edition at 14 euros, printed and digital version at 14 euros. It seems absurd: if the printed edition costs the same as the printed and online version together, why offer it?

Here is the answer

If you offer two possibilities: digital for 10 euros and printed (with or without digital version) for 14 euros; on average 80% of the subscribers will adhere to the first offer (digital) and 20% to the second.

If instead you offer three possibilities: digital version 10 euros, printed version 14 euros, printed and digital version 16 euros; nobody will choose the second offer, while the other two offers will record preferences similar to the previous case.

If instead you offer three possibilities: digital version 10 euros, printed version 14 euros, printed and digital version 16 euros; nobody will choose the second offer, while the other two offers will record preferences similar to the previous case.

But if you propose: digital for 10 euros, printed for 14, and printed and digital for 14; nobody will choose the second option, while the other two offers will invert the percentages: about 30% will choose only the digital version, while 70% will opt for the mixed option.

What happened? An apparently useless element (a less interesting offer at the same price of the more advantageous one) makes the more complete offer—offered at the same price—more appealing.

Is it a rational process? I would tend to say no, but this is actually what happened during the subscription campaigns of magazines like The Economist, the NY Times, etc.

This information will help you choose more freely the next time you subscribe to a magazine, but try to also think of how to use it actively to make important choices, favour group decisions, help someone who is resistant to change, overcome a communicative conflict or in other situations of stuckness or indecision.

Article by Fabio Sinibaldi and Sara Achilli